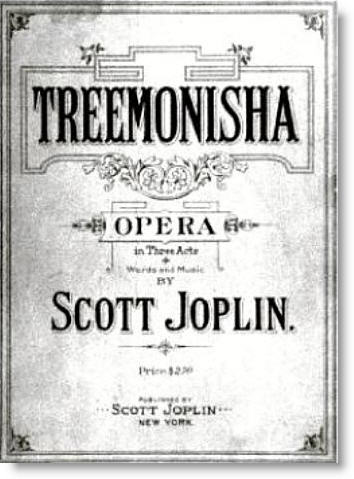

Scott Joplin is best known for his jaunty piano rags, including “The Entertainer,” “Solace” (works later featured on the soundtrack to the 1973 film “The Sting”) and, above all, “The Maple Leaf Rag.” But one of the most tantalizing and enigmatic portions of the composer’s legacy was his 1910 opera, “Treemonisha.” Reputedly all that remained of “Treemonisha” at the time of Joplin’s death in 1917 was a piano-vocal score, which he had published at his own expense in 1911.

In 1975, “Treemonisha” received a full-scale production by the Houston Grand Opera, for which the piano score was orchestrated by the eminent American composer, conductor and jazz scholar Gunther Schuller. In the liner notes to the resultant Deutsche Grammophon “original cast” recording of the opera, Vera Brodsky Lawrence (editor of Joplin’s “Collected Piano Works”) wrote that “Treemonisha” represented Joplin’s intention “to write a serious grand opera according to the accepted standards of his day.” Mr. Schuller’s orchestrations, tailored to fit an operatic cast and large chorus, are equivalent in instrumental heft to the modernized chamber orchestra of Richard Strauss’s 1912 opera “Ariadne auf Naxos.” The recording, and subsequent revivals of the Schuller arrangement of the score by Opera Theater of St. Louis in 2000 and New York’s Collegiate Chorale in 2006, apparently offered the last word on what seemed to be a melodious but stylistically naive work. Until now.

On Dec. 6, to mark the centenary of the Joplin piano score’s publication, New World Records is releasing an entirely new recording of “Treemonisha” that places it into a clearer ragtime perspective. The release, featuring Metropolitan Opera soprano Anita Johnson in the title role, includes a 118-page book and represents 18 years of research by its conductor, Rick Benjamin. Mr. Benjamin, the founder and director of the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra, is an authority and leading interpreter of ragtime music.

Having closely studied all available musical and historical sources related to the opera—including Joplin’s own instrumentation jottings in his personal copy of the piano score—Mr. Benjamin aimed to create a new, historically correct performing edition of the opera that would reflect the original musical character intended by Joplin. In 2003 Mr. Benjamin and the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra and singers premiered this version semistaged in San Francisco, and gave subsequent performances in recent years at the historic Saenger Theater in Joplin’s hometown of Texarkana, Texas, and at Cheyney University of Pennsylvania (America’s oldest black college) among other venues. Mr. Benjamin notes that he has also “allowed my edition to be produced by Opera Memphis and several other opera companies.”

The first thing listeners to this splendid new “Treemonisha” will note is its intimacy. Instead of grandiose voices and opera-scale orchestrations, this recording features lighter voices accompanied by the lighter orchestral textures of authentic ragtime instrumentation, based on the so-called “Eleven and Piano” ensemble. Consisting of flute (also doubling as piccolo), clarinet, two cornets, trombone, drums, piano, two violins, viola, cello, and double bass, with one instrument to a part, this nimble combination was the standard instrumental makeup of theater, minstrel-show and vaudeville orchestras from the 1870s to the 1920s. It was also the basis of early recording orchestras before the invention of the recording microphone.

Mr. Benjamin contends that the 1975 Houston revival “remodeled ‘Treemonisha’ into European-style grand opera—something it decidedly is not.”

Indeed, while “Treemonisha” may be considered Joplin’s response to European opera, the previous large-scale orchestration emphasized a stylistic conflict in its mixture of ragtime and other genres, none of them operatic. Although three ensemble numbers are ragtime masterpieces—”We’re Goin’ Around,” “Aunt Dinah Has Blowed De Horn” and the truly grand finale, “A Real Slow Drag”—the other numbers are composed in an idiom drawn from Gay ’90s balladry, barbershop quartet and gospel song rather than the accepted manner of Giuseppe Verdi or Giacomo Puccini. Moreover, the libretto’s simple language and action are far removed from the prevailing European dramatic style. It all raises the question of what Joplin himself meant by “opera.”

Joplin’s own terminology may have been partly to blame for earlier perceptions. Mr. Benjamin asserts that, “When he rather defensively stated in 1913 that ‘. . . the score complete is grand opera,’ he was simply emphasizing that the format was that of true opera—i.e., all-sung—and not the typical hodgepodge entertainments that many of his contemporaries were calling ‘operas’ with or without irony.”

Historically speaking, “Treemonisha” was composed while minstrel shows were still in fashion and blackface musical numbers were standard fare in vaudeville. General opera audiences, accustomed to African stage characters only as exotic royal heroines like the title characters of Verdi’s “Aida” and Giacomo Meyerbeer’s “L’Africaine,” would have taken scant interest in a moralizing work about a rural Arkansas community of former slaves led by a school teacher. But it might have appealed to black audiences at the time.

And this is Mr. Benjamin’s point. “Joplin’s oft-stated goal,” he says by telephone, “was to produce ‘Treemonisha’ at Harlem’s Crescent and Lafayette theaters—both African-American vaudeville houses—which suggests that his target audiences were black.

“Moreover, with all due respect to Gunther Schuller and the Houston Grand Opera,” Mr. Benjamin continues, “in 1911—decades before the Civil Rights Movement—Scott Joplin would never have had entrée into a major American opera company with a big orchestra.” On the contrary, “he wrote ‘Treemonisha’ specifically to offer an accessible operatic form to the middle- and working-classes, who attended vaudeville shows in neighborhood theaters.” Indeed, we can view “Treemonisha” as the ancestor to many works written today that are called operas by their composers, but which contain a great deal of rock, pop and other nonoperatic music.

Mr. Benjamin also says that his findings have also scotched the longstanding notion that “Treemonisha” was never performed complete in Joplin’s lifetime. “Joplin did in fact succeed in performing ‘Treemonisha’ for paying audiences in Bayonne, N.J., in 1913.” And he had himself orchestrated it. Mr. Benjamin’s essay includes his account of his 1989 meeting with the estate attorney who had personally thrown away three cartons of “Treemonisha” manuscripts, including band parts, in 1962 when Joplin was forgotten.

“‘Treemonisha,'” says Mr. Benjamin, “is truly a rare artifact of a vanished culture: an opera about African-Americans of the Reconstruction era—created by a black man who actually lived through it. As a unique work of art, it doesn’t fit the usual templates. It is the product of a great American genius, and we hope at least to help focus attention on what’s truly wonderful about it.”