The Liberty Song The Liberty Song

1768

Music by: William Boyce

Lyrics by: John Dickinson

Cover artist: none

Sources disagree on what may have been America’s first patriotic song. The authoritative New Grove Dictionary of American Music credits this song as the first true American patriotic song. However, other sources, in particular one closer to the times ( The American History and Encyclopedia of American Music, 1910) cites William Billings, as having published the first “war song” in his Singing Master’s Assistant. Within this work, one of the more important musical publications of its time, are found two compositions that became very popular with Revolutionary troops. The significance of the political agitation at this time presented opportunity for Billings to display his aptitude and keen intuition of the temper of the times, and his compositions are an outburst of the patriotic fervor that had been awaiting just such opportunity for development. So to his favorite tune of Chester he set the following text:

Let tyrants shake their iron rod,

And slavery clank her galling chains,

We’ll fear them not, we’ll trust in God;

New England’s God forever reigns.The foe comes on with haughty stride,

Our troops advance with martial noise;

Their veterans flee before our arms.

And generals yield to beardless boys.

Naturally enough, these words, set to a familiar tune and so thoroughly characteristic of the spirit of the hour, caught the taste of the people. Indeed, these half sacred, half secular works may be classed as our pioneer patriotic and popular music.

Several other sources and the New Grove cite The Liberty Song as the seminal American patriotic song. Published at first only as text in the Boston Chronicle in 1768 (cover image is of the particular page). The writer, John Dickinson used the music from William Boyce’s song Heart of Oak. The uniqueness of this work and it’s permanence in our language comes from the line: “By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall,” the first recorded use of that sentiment that has remained with us for over 234 years. A simple song, yet you can see from the lyrics it is full of strong sentiments and sets a fine example for all the patriotic music that has followed. Dickinson was not a songwriter or composer (see below biography) but did have a way with words and as a fervent architect of our freedom, wrote the words to this song to encourage people to contribute to the cause of the Revolution.

William Boyce (1710 – 1799) Boyce is best known as one of England’s greatest dramatic composers. He was an accomplished organist and studied under a number of luminaries of the period. He was appointed composer to the Chapel Royal and the King in 1736 and the following year was chosen as the composer for the Gloucester, Worcester and Hereford choir music festival. In 1758 he became organist at the Chapel Royal. He held a doctorate of music from Cambridge and composed a number of works that are still in the repertoire. Among them are twelve symphonies, a violin concerto and a number of oratorios.

John Dickinson (1732 – 1808) is perhaps one of the least likely people you would expect to have been a songwriter. One of America’s founding fathers and a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, Dickinson is more remembered for his contributions to the building of our country than as a songwriter. His family were English, having settled in the seventeenth century in Maryland; Dickinson himself was born in Talbot County, on November 8, 1732. He grew up at Poplar Hall, the elegant brick mansion of his father, Judge Samuel Dickinson. His initial education consisted of private tutelage but later his parents sent him to London for a proper education. In London he studied law and returned home to practice law in Philadelphia. It was at this time he became involved in politics and was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly. He distinguished himself in the Assembly, siding with the Proprietary party against the faction led by Benjamin Franklin that sought to turn Pennsylvania from a commonwealth governed by the Penn family to a colony immediately under Royal control. Dickinson, eloquent and stubborn, stood his ground and kept his standing in Philadelphia society.

Later, elected to the Continental Congress, Dickinson proved his skill in drafting declarations in the name of the Congress. One notable one was written with Thomas Jefferson, “Declaration on the Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms,” with a conclusion that Americans were “resolved to die freemen rather than live slaves.” When Richard Henry Lee proposed a declaration on independence, Dickinson opposed it, saying the timing was bad. Dickinson suggested the colonies form a confederation amongst themselves before declaring independence from the Crown. While Jefferson, Franklin, John Adams, and others were appointed to a committee to draft a Declaration of Independence, Dickinson, Roger Sherman, and others were put on a committee to draw up Articles of Confederation. The document Dickinson prepared was heavily amended and revised before being accepted by the full Congress.

When the war began, Dickinson enlisted as a private in the Continental Army, having been a colonel in the provincial militia. Dickinson’s company served under General Caesar Rodney, notably at the Battle of Brandywine. In 1781 Dickinson was elected president of Delaware; the next year he resigned that post to be elected president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. While Dickinson was president of Pennsylvania, his old colleague from the Congress, Benjamin Rush, suggested founding a new college in Cumberland County. Rush approached Dickinson about naming the new college “John and Mary’s College,” in honor of the president and his lady. Dickinson, appalled at the parallel with William and Mary, demurred, saying that the new Republic should avoid allusions to monarchy. Rush won approval for calling the college “Dickinson.”

The 1790s saw Dickinson in retirement, living with his wife and two daughters in a townhouse in Wilmington, Delaware. John Dickinson died February 14, 1808, at his home in Wilmington. President Jefferson expressed his sorrow, and both houses of Congress resolved to wear black armbands in mourning. He was buried in the cemetery of the Friends Meeting House, Wilmington.

|

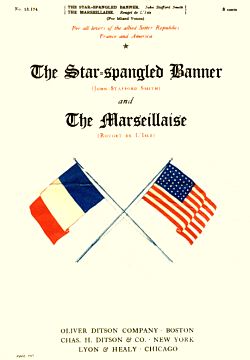

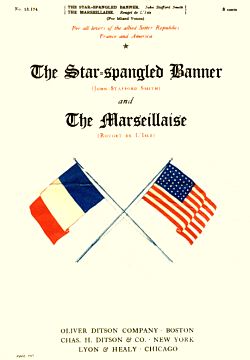

The Star Spangled Banner The Star Spangled Banner

1814

Music by: John Stafford Smith

Lyrics by: Francis Scott Key

Cover artist: unknown

The National Anthem of the United States is perhaps one of the most recognized and well known anthems in the world. Loved by Americans for its beauty but hated by singers for it’s difficult leaps and range, there can still be no doubt that this is one of the most inspiring pieces of music ever written. Most Americans can sing the first verse from memory, but I suspect few of us can even begin the second verse and fewer still are aware that there was a third verse (you can see the full lyrics at the link below). The words to the Star Spangled Banner were written in 1814 by Francis Scott Key, a Washington lawyer. Key had arranged the release from prison of a friend during a truce and was aboard a ship on the night of 13-14 September. During this night there was a bombardment of Fort McHenry at Baltimore and Key watched it from the ship. The bombardment stopped and supposedly Key paced the deck the remainder of the night wondering if “our flag was still there.” When dawn came and he saw that the flag was indeed still there, he wrote a poem about the experience.

As with the Liberty Song, this work used an existing melody by another English organist, John Stafford Smith. On his return to Baltimore, Key requested a friend, Thomas Carr to adapt his poem to the melody of Smith’s To Anacreon in Heaven and once done, the song was immediately published in broadsides and newspapers of the day. Interestingly, Smith studied with Boyce, the composer of the melody of the Liberty Song. The first printings of the “Banner” were actually untitled and it was only published as Defense of Fort McHenry. The title we now know was added later.

The song was adopted as our National Anthem only in 1931 but the song has endured criticism over the years. It’s difficulty in singing has prompted frequent calls for a new anthem and earlier, it was often criticized for having a melody that is the product of a foreigner. However, because of it’s patriotic association and quality, it has endured the test of time and will no doubt remain our national song forever.

John Stafford Smith (1750 – 1836), composer of the melody to the Star Spangled Banner, was an English organist, composer and talented tenor born in Gloucester. He studied under his father who was organist at Gloucester Cathedral and William Boyce, composer of the Liberty Song melody. Organist for the Chapel Royal and a vicar at Westminster Abbey, Smith composed numerous anthems, chants and songs. A musical scholar, Smith also edited one of the best collections of early music, The Musica Antiqua. Smith died in London in 1836.

Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) was born in Frederick, Maryland, and after an education at St. John’s College, Annapolis, he worked as an attorney, first in his home town, and then in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. In 1814 the British seized Dr. William Beanes in retreat from Washington, and Key was dispatched to arrange his release. This accomplished, Key spent the night of September 13-14 on an American ship as the British shelled Baltimore. In The Star-Spangled Banner, written on an envelope as he was taken ashore and revised in his hotel after night fell, Key recorded his feelings when dawn broke and the American flag still flew. His sister-in-law, Mrs. Joseph Hopper Nicholson, took it to a printer the next day. After being published on handbills, the anthem was printed in the Baltimore American on September 21. The manuscript copy now rests in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. This poem was not Key’s only effort; his Poems were posthumously published in 1857. Married to Mary Tayloe Lloyd in 1802, Key had 11 children. He died on January 11, 1843, and was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick. Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) was born in Frederick, Maryland, and after an education at St. John’s College, Annapolis, he worked as an attorney, first in his home town, and then in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. In 1814 the British seized Dr. William Beanes in retreat from Washington, and Key was dispatched to arrange his release. This accomplished, Key spent the night of September 13-14 on an American ship as the British shelled Baltimore. In The Star-Spangled Banner, written on an envelope as he was taken ashore and revised in his hotel after night fell, Key recorded his feelings when dawn broke and the American flag still flew. His sister-in-law, Mrs. Joseph Hopper Nicholson, took it to a printer the next day. After being published on handbills, the anthem was printed in the Baltimore American on September 21. The manuscript copy now rests in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. This poem was not Key’s only effort; his Poems were posthumously published in 1857. Married to Mary Tayloe Lloyd in 1802, Key had 11 children. He died on January 11, 1843, and was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick.

|

America Forever America Forever

1898

Music by: E.T. Paull

Lyrics by: H.A. Freeman

Cover artist: A. Hoen Litho.

Patriotic songs continued to flourish throughout the 19th century, the American Civil War perhaps being one of the more prolific periods where both the South and the North generated numerous songs to stir patriotic feelings. After that war, most of the Patriotic music focused on rebuilding America and consolidating a united front. Other wars of course came and went during that century but perhaps the first real test of American resolve after the Civil War came with the Spanish American War of 1895 – 1902.. This march with lyrics is one of the grandest expressions of unity that I’ve seen. As with most Paull works, it is expansive seems to go on forever.

ET Paull (link to in-depth biography) was one of America’s patriotic march and musical greats, his marches were full of spirit and patriotism that have been matched by few others. This work, featured before in our feature of E. T. Paull works is one of Paull’s greatest and more unusual works in that Paull has included lyrics. In general, almost all of Paull’s works are piano solo and only two or three contain lyrics. In this one Paull also included a bonus at the end; an arrangement of America that makes this entire work just ooze with patriotism. If you are an American, you have to love this work! Make no mistake though, this is not a song in the normal sense, it is still very much a march and even though it has a nice chorus that is very reflective of songs of the day, it also very unusually then transitions into a trio, then repeats, then transitions to the version of America. The sheet music cover shows the work available as a Piano solo, four hand or Song version. It would play just as well as a piano solo march. Musically, this is one of Paul’s best.

ET(Edward Taylor) Paull (February 16, 1858 – November 27, 1924) Was the son of Virginia farmers and started his musical career as manager of a music store, selling pianos and organs in Martinsburg , Virginia around 1878. It is unclear as to his activities for the next 20 years but his first successful march was The Chariot Race or Ben Hur March (MIDI) in 1894. The great success of this march caused Paull to begin a steady stream of works. He started his own publishing company around this same period and continued publishing under his name till his death (at which time the company was bought and continued to publish under the same name for two years afterward). Though best known today for his marches, Paull did write other works and even wrote one piece for silent film Armenian Maid in 1919. Marches were wildly popular and though Paull was capable of composing fine works, he often obtained works by others and arranged them and released them under his banner. This work is one such work. His last work was the 1924, Spirit Of The U.S.A., copyrighted just six weeks before his death. ET(Edward Taylor) Paull (February 16, 1858 – November 27, 1924) Was the son of Virginia farmers and started his musical career as manager of a music store, selling pianos and organs in Martinsburg , Virginia around 1878. It is unclear as to his activities for the next 20 years but his first successful march was The Chariot Race or Ben Hur March (MIDI) in 1894. The great success of this march caused Paull to begin a steady stream of works. He started his own publishing company around this same period and continued publishing under his name till his death (at which time the company was bought and continued to publish under the same name for two years afterward). Though best known today for his marches, Paull did write other works and even wrote one piece for silent film Armenian Maid in 1919. Marches were wildly popular and though Paull was capable of composing fine works, he often obtained works by others and arranged them and released them under his banner. This work is one such work. His last work was the 1924, Spirit Of The U.S.A., copyrighted just six weeks before his death.

|

You’re A Grand Old Flag You’re A Grand Old Flag

1906

Music by: George M. Cohan

Lyrics by: Cohan

Cover artist: Rose Symbol

Once the Tin Pan Alley phenomenon began, American music took on a different nature and more of our music took on a mass appeal structure. Patriotic music began to follow this trend and perhaps no other American popular song composer did more to popularize the patriotic song than George M. Cohan. George Washington Jr., was one of Cohan’s many stage works that found a great deal of popularity. Arguably, this work may have been the one that really propelled him into the limelight and made him a superstar. Unquestionably, this song (and Over There (scorch)) is one of his top tunes and one that has been heard regularly over almost 100 years. The show first opened on Feb. 12, 1906 at the Herald Square Theater. Written entirely by Cohan and starring himself in the title role and including Helen (his mother) and Jerry Cohan (brother), the show was a tremendous hit. It was in this show that Cohan introduced an act that he would always be identified with; he would march up and down the stage with an American flag as he sang this song.

George M. Cohan was born in Providence, RI on either the 3rd or 4th of July 1878. Cohan always used the 4th as his birthday and it certainly served him well to do so throughout his career and after as he became our “Yankee Doodle Boy”. From boyhood, he toured New England and the Midwest with his parents and sister in an act called The Four Cohans. By 1900, the Cohans were one of the leading acts in vaudeville. He also played the violin, wrote sketches for the family show and started writing songs by age 13. It was during these early years that he adopted the swaggering and brash image that was so well portrayed by Cagney. His first original musical was Little Johnny Jones (1904), which he wrote entirely himself and in which he starred as the lead. It was successful and included the hit Yankee Doodle Boy and Give My Regards To Broadway (Scorch format). In 1906, his reputation was improved more with the productions George Washington Jr., and Forty-five Minutes From Broadway. George M. Cohan was born in Providence, RI on either the 3rd or 4th of July 1878. Cohan always used the 4th as his birthday and it certainly served him well to do so throughout his career and after as he became our “Yankee Doodle Boy”. From boyhood, he toured New England and the Midwest with his parents and sister in an act called The Four Cohans. By 1900, the Cohans were one of the leading acts in vaudeville. He also played the violin, wrote sketches for the family show and started writing songs by age 13. It was during these early years that he adopted the swaggering and brash image that was so well portrayed by Cagney. His first original musical was Little Johnny Jones (1904), which he wrote entirely himself and in which he starred as the lead. It was successful and included the hit Yankee Doodle Boy and Give My Regards To Broadway (Scorch format). In 1906, his reputation was improved more with the productions George Washington Jr., and Forty-five Minutes From Broadway.

Cohan continued to write and star in musical comedies into the 1920’s but at the same time had formed a publishing house in collaboration with Sam Harris with whom he also opened a number of playhouses and theaters including the George M. Cohan Theater in New York. Cohan wrote over 500 songs and it is said that Over There (Scorch format) was the most popular morale song for BOTH world wars. Interestingly, Cohan was untrained as a musician and he professed to write only simple songs with simple harmonies and limited ranges. Regardless, his contribution to vaudeville, musical theater and popular music is undeniable and profound. Cohan died in New York on November 5, 1942.

|

The Good Old U.S.A. The Good Old U.S.A.

1906

Music by: Theodore Morse

Lyrics by: Jack Drislane

Cover artist: unknown

Not only was the flag or our country saluted with patriotic songs but great Americans were also often honored with songs. Most of the time, historic political figures were honored but just about anyone was fair game. This song is somewhat unique in that it honors William Randolph Hearst, a businessman. A very upbeat march tempo song, the lyrics have absolutely nothing to do with Hearst. Rather it speaks of the past wars and luminaries such as Washington and Jackson and our patriotic musical heritage.

Apparently, Morse and Drislane were fans of Hearst and dedicated this song to him as a tribute to him. Hearst (1863-1951) inherited a fortune and a newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner and from it created one of the greatest media empires this country has ever known. Inspired by the journalism of Joseph Pulitzer, Hearst turned the newspaper into a combination of reformist investigative reporting and lurid sensationalism. He soon developed a reputation for employing the best journalists available. Hearst was a member of the United States House of Representatives (1903-07). His national chain of newspapers and periodicals grew to include the Chicago Examiner , Boston American , Cosmopolitan, and Harper’s Bazaar . His life inspired the Orson Welles film Citizen Kane.

Theodore F. Morse (b. 1873, Washington, D.C., d. 1924, New York, N.Y.) was one of the most important composers of the period before and up to the First World War. He wrote many, many popular songs as well as the scores to several popular  stage shows. His wife, Theodora Morse was also an accomplished composer and performer who often composed under the name of Dorothy Terriss. Theodore Morse was a privately tutored student of piano and violin and began his education at the Maryland Military Academy. At age 14 (1887), he ran away from the Academy and went to New York where he became a clerk in a music store. His first song was sold when be was only 15 and by age 24 he had his own publishing house, The Morse Music Co, which was in existence from 1898 to 1900. Morse is well represented on ParlorSongs and has a long list of popular hits to his credit. Among his most famous works are, Blue Bell (1904), M-O-T-H-E-R (1915), Down In Jungle Town (1908) and Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here (1917). In 1903, Morse wrote Hurray For Baffin Bay for a new stage show that would become the basis for a blockbuster movie, The Wizard of Oz. stage shows. His wife, Theodora Morse was also an accomplished composer and performer who often composed under the name of Dorothy Terriss. Theodore Morse was a privately tutored student of piano and violin and began his education at the Maryland Military Academy. At age 14 (1887), he ran away from the Academy and went to New York where he became a clerk in a music store. His first song was sold when be was only 15 and by age 24 he had his own publishing house, The Morse Music Co, which was in existence from 1898 to 1900. Morse is well represented on ParlorSongs and has a long list of popular hits to his credit. Among his most famous works are, Blue Bell (1904), M-O-T-H-E-R (1915), Down In Jungle Town (1908) and Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here (1917). In 1903, Morse wrote Hurray For Baffin Bay for a new stage show that would become the basis for a blockbuster movie, The Wizard of Oz.

|

National Emblem National Emblem

1907

Music by: E.E. Bagley

Lyrics by: None, piano solo

Cover artist:

Perhaps the most prolific and most memorable patriotic works are the many marches that were penned by great American composers over the course of our history. It is the marches that are played at parades, festivals, military expositions and fireworks celebrations on Independence Day. Of course, the king of American marches was John Phillip Sousa and his famous Stars And Stripes Forever (MIDI) is perhaps the most famous march of them all. Regardless of Sousa’s fame, there were hundreds of other grand marches composed by fine composers and among them is E.E. Bagley’s National Emblem. This march is easily the equal of Stars and Stripes and is also one of the most popular and often played marches from our early musical heritage.

One reason for the success of this song is that Bagley quoted freely from the The Star Spangled Banner and wove a terrific musical tapestry around that melody as well as many of his own original and memorable melodies. However, Bagley begins in Eb with an introduction that really catches your attention and then transitions to The Star Spangled Banner where Bagley uses the first twelve notes of it in duple, rather than triple time. Once the quote from the Star Spangled Banner is used, all of the other melodic material in this march are Bagley’s. A stirring and musically enjoyable work, this march certainly deserves a place in the American patriotic musical hall of fame. It has been said that “National Emblem is one of America’s most ‘perfect’ marches, causing the false impression that it was written by Sousa.” Legendary brass band and orchestral conductor Frederick Fennell said of this piece, “It is a march for marching; sit-down performances of it should continue to march, for that is its heritage – music for the feet, not the head – and it is unmistakably music for the spirit!”

Edwin Eugene Bagley (1857 – 1922) Was one of Americas most eminent bandmasters and composer of marches. His most famous march is the National Emblem however many of his marches are still quite popular today and are frequently played at military ceremonies. The tune to the National Emblem was used in a novelty song, And The Monkey Wrapped His Tail Around The Flagpole.

Bagley began his music career at the age of nine as a vocalist and comedian with Leavitt’s Bellringers, a company of entertainers that toured many of the larger cities of the United States. He began playing the cornet, traveling for six years with the Swiss Bellringers, after which time he joined Blaisdell’s Orchestra of Concord, New Hampshire. In 1880, he came to Boston as a solo cornetist at the Park Theater. For nine years, he traveled with the Bostonians, an opera company. While with this company, he changed from cornet to trombone. He performed with the Germania Band of Boston and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. By this time he had already composed many marches, including Front Section, The Imperial, The Ambassador, and America Victorious. Bagley never took a lesson on any musical instrument. He was also a fine artist who could have made a name for himself as a caricaturist.

|

The Flag That’s Yours And Mine The Flag That’s Yours And Mine

1909

Music by: Henry A. Stone

Lyrics by: Stone

Cover artist: unknown

This song, dedicated to the Cambridge (Mass., I assume since the publisher was in Boston) Lodge, no. 839 of the B.P.O. Elks, is a wonderful example of the kinds of patriotic songs that were written during the first decade of the twentieth century. They have a fervent, almost innocent and naïve quality that is refreshing. During those times, love of country and patriotism were rampant and though our government was not perfect, people tended to put more faith in it and forgive the flaws. Faith in the country and pride in the flag were common public expressions and efforts to improve our country were constructively focused.

This piece begins with a stirring broad anthem that is pleasant and very singable. The Chorus is an upbeat march tempo that is brief yet memorable. Given the simple beauty of this work, I’m a little surprised it has not survived as a part of the standard repertoire of patriotic songs in America. It’s brevity and construction make for an easily remembered song.

Henry A. Stone is another of our “lost” songwriters from the period. There was a Henry Asaf Stone, born in 1883, in New York,, NY, who died in 1957 but I’m unable to confirm that this is the Stone who wrote this song. Unfortunately, many of the regional songwriters whose songs were printed in regional or local areas never reached the level of fame or exposure that the mainstream Tin Pan Alley composers did.

|

Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) was born in Frederick, Maryland, and after an education at St. John’s College, Annapolis, he worked as an attorney, first in his home town, and then in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. In 1814 the British seized Dr. William Beanes in retreat from Washington, and Key was dispatched to arrange his release. This accomplished, Key spent the night of September 13-14 on an American ship as the British shelled Baltimore. In The Star-Spangled Banner, written on an envelope as he was taken ashore and revised in his hotel after night fell, Key recorded his feelings when dawn broke and the American flag still flew. His sister-in-law, Mrs. Joseph Hopper Nicholson, took it to a printer the next day. After being published on handbills, the anthem was printed in the Baltimore American on September 21. The manuscript copy now rests in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. This poem was not Key’s only effort; his Poems were posthumously published in 1857. Married to Mary Tayloe Lloyd in 1802, Key had 11 children. He died on January 11, 1843, and was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick.

Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) was born in Frederick, Maryland, and after an education at St. John’s College, Annapolis, he worked as an attorney, first in his home town, and then in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. In 1814 the British seized Dr. William Beanes in retreat from Washington, and Key was dispatched to arrange his release. This accomplished, Key spent the night of September 13-14 on an American ship as the British shelled Baltimore. In The Star-Spangled Banner, written on an envelope as he was taken ashore and revised in his hotel after night fell, Key recorded his feelings when dawn broke and the American flag still flew. His sister-in-law, Mrs. Joseph Hopper Nicholson, took it to a printer the next day. After being published on handbills, the anthem was printed in the Baltimore American on September 21. The manuscript copy now rests in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. This poem was not Key’s only effort; his Poems were posthumously published in 1857. Married to Mary Tayloe Lloyd in 1802, Key had 11 children. He died on January 11, 1843, and was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick.

ET(Edward Taylor) Paull (February 16, 1858 – November 27, 1924) Was the son of Virginia farmers and started his musical career as manager of a music store, selling pianos and organs in Martinsburg , Virginia around 1878. It is unclear as to his activities for the next 20 years but his first successful march was

ET(Edward Taylor) Paull (February 16, 1858 – November 27, 1924) Was the son of Virginia farmers and started his musical career as manager of a music store, selling pianos and organs in Martinsburg , Virginia around 1878. It is unclear as to his activities for the next 20 years but his first successful march was

George M. Cohan was born in Providence, RI on either the 3rd or 4th of July 1878. Cohan always used the 4th as his birthday and it certainly served him well to do so throughout his career and after as he became our “Yankee Doodle Boy”. From boyhood, he toured New England and the Midwest with his parents and sister in an act called The Four Cohans. By 1900, the Cohans were one of the leading acts in vaudeville. He also played the violin, wrote sketches for the family show and started writing songs by age 13. It was during these early years that he adopted the swaggering and brash image that was so well portrayed by Cagney. His first original musical was Little Johnny Jones (1904), which he wrote entirely himself and in which he starred as the lead. It was successful and included the hit Yankee Doodle Boy and

George M. Cohan was born in Providence, RI on either the 3rd or 4th of July 1878. Cohan always used the 4th as his birthday and it certainly served him well to do so throughout his career and after as he became our “Yankee Doodle Boy”. From boyhood, he toured New England and the Midwest with his parents and sister in an act called The Four Cohans. By 1900, the Cohans were one of the leading acts in vaudeville. He also played the violin, wrote sketches for the family show and started writing songs by age 13. It was during these early years that he adopted the swaggering and brash image that was so well portrayed by Cagney. His first original musical was Little Johnny Jones (1904), which he wrote entirely himself and in which he starred as the lead. It was successful and included the hit Yankee Doodle Boy and

stage shows. His wife, Theodora Morse was also an accomplished composer and performer who often composed under the name of Dorothy Terriss. Theodore Morse was a privately tutored student of piano and violin and began his education at the Maryland Military Academy. At age 14 (1887), he ran away from the Academy and went to New York where he became a clerk in a music store. His first song was sold when be was only 15 and by age 24 he had his own publishing house, The Morse Music Co, which was in existence from 1898 to 1900. Morse is well represented on ParlorSongs and has a long list of popular hits to his credit. Among his most famous works are,

stage shows. His wife, Theodora Morse was also an accomplished composer and performer who often composed under the name of Dorothy Terriss. Theodore Morse was a privately tutored student of piano and violin and began his education at the Maryland Military Academy. At age 14 (1887), he ran away from the Academy and went to New York where he became a clerk in a music store. His first song was sold when be was only 15 and by age 24 he had his own publishing house, The Morse Music Co, which was in existence from 1898 to 1900. Morse is well represented on ParlorSongs and has a long list of popular hits to his credit. Among his most famous works are,

Leave a reply